This week we're going to turn the technology clock forward a little bit and look at Roberta Williams'

The Colonel's Bequest, published by Sierra in 1989. It's a murder mystery set in New Orleans, circa 1925, and is initially presented as if it were an Agatha Christie play; its themes recall the very first Sierra Hi-Res Adventure,

Mystery House, also by Williams

. The game introduced a new character, young investigative reporter Laura Bow, who also appeared in the 1992 sequel,

The Dagger of Amon-Ra. In this story, Laura is invited to her friend Lillian's family estate for the weekend, and is drawn into a web of intrigue coalescing around ailing Uncle Henri's will.

I bought

The Colonel's Bequest when it first came out, but never finished it properly, so it's high time I gave it some more serious attention. The game runs on the Sierra Creative Interpreter, the second generation of Sierra's 3-D illustrated, animated adventure game technology -- the graphics resolution is doubled compared to the original Adventure Game Interpreter used for

King's Quest and its descendants. The graphics engine is still limited to 16 colors, and background graphics are still drawn using vectors and fills; the early SCI games really pushed that image technology to its limits. The game also supports more sophisticated music and atmospheric sound effects, with support for a variety of sound cards and MIDI modules, but does not yet handle sampled audio.

I was surprised at how much

The Colonel's Bequest feels like its text adventure ancestors -- while Laura moves through the scenery like a videogame character, there's still a lot of typing and reading. A parser is used to interact with objects and people, and there are detailed text descriptions of most visible rooms and objects, even when they aren't directly relevant to the gameplay. Since this is an animated adventure, however, Laura's positioning is often important -- she will refuse to closely examine or interact with an object if she isn't close enough to it, or even facing in the wrong direction; generally this is so the animation will display properly. Also, Laura's many possible deaths are sudden and often unexpected -- the kinder, gentler approach of later point-and-click graphic adventures is nowhere to be seen here.

The Colonel's Bequest feels a bit like the Infocom text mysteries (e.g.

The Suspect and

Witness), but the fundamental structure is different. The story progresses in eight one-hour acts (rather long for a play, granted), each divided into four "fifteen minute" segments. Protagonist Laura Bow doesn't actually drive the plot -- rather, it unfolds around her, and her job is to use her observational and puzzle-solving talents to gather as much information and evidence as possible. Time itself is elastic, moving forward only when the player makes a key discovery. Characters are put in specific places, doing specific things during each segment, with no direct reference to passing time; Laura is free to explore for hours between significant events if the player so chooses.

The game can actually be finished by simply wandering around the estate looking for each milestone occurrence; the story will move forward until it reaches a conclusion, whether Laura is accomplishing what she's supposed to or not. Of course, there's more than one ending, and even when the best one is achieved, the game's detailed rating of Laura's investigative skills, or lack thereof, may inspire a replay.

I ran

The Colonel's Bequest on a modern PC using DOSBox with Adlib sound card emulation, just as I did back in the day. One disadvantage I (re)discovered is that it takes a lot longer to play an animated adventure than a text adventure, if only because so much time is spent physically navigating the environment even when you know what you want to do. There's no way to execute a quickly typed sequence like N/N/E/GET LAMP/W/S/D. But I wasn't annoyed by the more deliberate pacing -- it seemed perfectly appropriate to an old dark house mystery.

This one is fun to play, and has significant replay value if you like mysteries. The Laura Bow games were not re-released in the Vivendi/Sierra box sets a few years back, unfortunately. If you plan to play the game yourself, which I do encourage, you may wish to stop reading here lest I give anything away.

****** SPOILERS AHEAD! *******

King's Quest, Space Quest, Police Quest, The Colonel's Be... quest. Tradition!

Like most old-fashioned mysteries, this is a melodrama at heart -- the characters are not treated naturalistically, but are clearly and strictly defined by their mode of dress and style of dialogue. Celie, the African-American cook, is given an Aunt Jemima kerchief and a text-rendered accent rife with stereotype:

There are even a few "suhs" thrown into her dialogue for period flavor. But Celie is a sympathetic character, and the portrayal is ultimately no more offensive than the

fromagesque accent of Fifi zee French maid.

The parser is very solid compared to early text adventures and the Sierra AGI generation; I didn't run into many unrecognized verbs, and the noun list is impressively thorough, covering almost all visible objects. The game also makes (indeed requires) intelligent use of "look in/behind/through" constructs, which makes Laura's work seem much more investigative than the simple LOOKs of old. The only frustration was that Laura can only pick up a handful of useful objects -- most can be looked at, but "belong to" someone or something and cannot be taken, so the puzzle-solving is a bit on the easy side, as most props are eliminated from consideration.

The game doesn't feature many puzzles in the traditional adventuring sense -- there are several, but the game can be finished without truly solving any of them; the game's overall arc relies more on watching, eavesdropping and examining telltale evidence. Getting a perfect rating is very difficult and requires being in the right places at exactly the right times, so an initial playthrough to map out the story will help a lot on subsequent attempts. Fortunately, the game is forgiving, and most of what the game has to offer can be experienced without coming anywhere close to a decent final rating.

The game is played fairly straight, but it still has a sense of humor. If Laura tries to use the toilet while another character is in the bathroom, the game haughtily informs us that this is NOT a

Leisure Suit Larry game. If she is alone, the game discreetly shoos us out of the bathroom while Laura attends to private matters. Note that none of this scatological activity is required to finish the game -- it's just there for fun. The bathroom also hosts an entertaining death sequence -- if Laura takes a shower, she undresses (discreetly turning her back, revealing a pert pixellated bottom), then gets stabbed to death a la

Psycho.

Laura dies in a number of entertaining ways, most of which are unforeseeable -- she can't swim, for instance, and will drown if she falls or walks into the smallest patch of bayou water. She can be killed by the murderer, run down by a horse, fatally tumbled down a dark staircase, cut clean down the middle by a falling axe, and felled by a falling chandelier. If she falls down the laundry chute, she posthumously reappears, rising through the roof as a harp-plucking angel. Her most comical death occurs by belltower -- after oiling the bell, and finding a cane to enable pulling the rope to ring it from below, Laura pulls the bell squarely onto her own head. In an anatomically improbable animation sequence, the bell emerges from the tower with Laura's feet sticking out of it, runs into a tree, and keels over.

Production values are quite high -- there's lots of incidental animation for actions unrelated to the game's plot, such as petting the dog, spinning a globe, and washing one's hands. Laura's feet splash when she walks through puddles, and the bayou frogs and alligators are very nicely animated by the standards of the day.

There's no real musical score, though a player piano and a couple of victrolas provide some spot entertainment with vintage ragtime and popular songs, and players are treated to a funky extended arrangement of "Camptown Races" if Laura spends enough time goofing around with the player piano. The atmospheric sound effects aren't always successful on the Adlib -- crickets and white-noise wind sound okay, but frogs and horses seem to be suffering from flatulence, running water sounds like wind chimes, and the thunder and lightning just sound clangy and weird.

"Look" can be position sensitive -- examining an object from a different angle sometimes reveals additional detail. Fortunately, on-screen clues help indicate that this is worth doing.

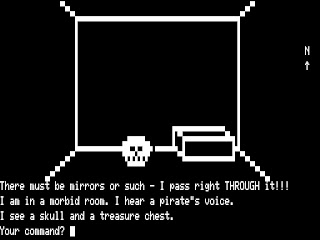

In classic style, every dead body Laura discovers disappears by the time she returns, and nobody will believe that any other person has died, despite the fact that they haven't seen him or her lately. I believe the game "cheats" a bit in this regard - I'm pretty sure that during some segments, certain characters are actually NOWHERE to be found in the game. At least the corpse-finding moments are enthusiastically played:

The only parser glitch I ran into was that while hiding in the secret areas between rooms, where paintings with suspiciously hollow eyes allow Laura to spy on the others,

"look painting" produces

"You can't see any painting here" even though the paintings are clearly visible on the other side of the cutaway display. It took me a while to figure out that facing up or down, then typing

"look through eyes" works.

Characters can be asked or told about each other and various objects, but some important clues can't be used in conversation. For example, the racehorse "Sunny Boy", circled on the late Dr. Wilbur Feels' racing form, is an unuseable reference, even though it seems like someone should have a recollection of the name.

Laura's friend Lillian is not very subtly portrayed. She seems quite normal when she invites Laura to the estate, then becomes very standoffish. Eventually she is found talking to her old dolls in a playhouse, near a chalkboard with seven hash marks on it. Hmmmmm.

While Laura is quite scrupulous about respecting people's belongings in general, she is perfectly willing to confiscate important objects from their dead bodies. Of course, our tee-totaling heroine may not be as squeaky-clean as she appears -- this may not be

Leisure Suit Larry, but Laura Bow is apparently quite the voyeur. She's only too happy to watch Fifi changing and see Jeeves the butler shirtless:

The game offers some useful hints after a less-than-perfect playthrough, which is a nice touch. I only achieved the "Absent Minded" rating, about halfway up the scale. Clearly I discovered the secret passages far too late to make good use of them, and was not as thorough in my snooping as I could have been.

Beyond the detailed rating scale, there are two possible story endings, determined primarily by the player's actions in Act VIII. The weaker conclusion sends Laura home with a muddled understanding of the night's events, as she wonders whether the story she was told by the only surviving family member is true. The better ending can be rescued from the ashes at the last minute if the player moves quickly enough after discovering the last corpse -- it's the only situation where real clock time has an impact on the story. This is the good one:

So that's

The Colonel's Bequest, from Sierra's Roberta Williams and a large team of artists, animators and composers. Next time, we'll get back to something a little more retro.