Thanks to everyone who took time to welcome me back! I'm still going through a backlog of comments and sorting out the bitcoin/gambling spam from the genuinely meaningful and informative comments the system has been gathering while I've been away, but I do hope to write a new post now and then.

(As to where my time has been going these past several years, I've been doing quite a bit of acting in various projects, which I may or may not owe to becoming more comfortable on camera doing my video podcasts here. The pandemic has forced/encouraged me to do less live theatre and more film and television work; if you want to know more, here's my IMDb page.)

Anyway, as time has gone on, I've realized this age of "Let's Play" videos makes the type of post I often write about my detailed experiences playing a specific game less relevant. I'll still write about obscure games that aren't likely to be covered elsewhere, but there are definitely games that are very well documented at this point.

So this post will be an attempt at a lighter approach, and honestly one that gives me a little more freedom to enjoy the ride without having to take detailed notes and capture screenshots. I've recently played through Revolution Software's classic Broken Sword 1 - The Shadow of the Templars: Director's Cut, a more seriously-styled point-and-click adventure originally released in 1992. I played the 2010 Director's Cut edition simply because that's the version I had picked up on Steam at some point; it adds some additional story and puzzles fleshing out Nico's story, but many people prefer the 1992 version as some content was changed/cut and puzzles simplified in this version.

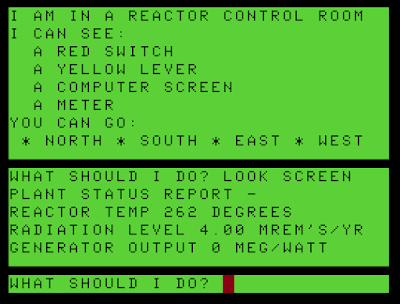

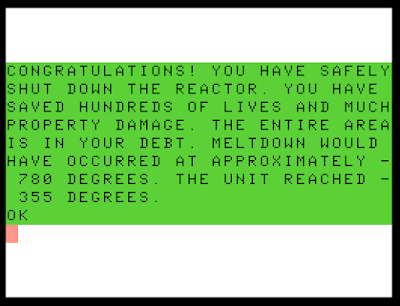

One historical note I'd like to make is that Revolution Software founder and Broken Sword creator Charles Cecil did his initial adventure game work on text adventures for Artic Computing and eventually became director of the company. I haven't been able to confirm this independently, but MobyGames credits him as the designer (which in 1982 likely also meant programmer) of Artic Adventures B - Inca Curse, C - Ship of Doom, and D - Espionage Island, which I've covered here in the past. As head of Revolution Software he pioneered the company's Virtual Theatre engine, which has hosted many notable games including the early Broken Sword titles and the classic Beneath A Steel Sky, an excellent sci-fi adventure that is now on my shortlist to tackle sometime.

I'll also note that while I never played Broken Sword 1 on PC back in the day, I did take a run at the Game Boy Advance cartridge version a decade or two back. I never finished it or even got very far into the story -- the game's beautiful high-resolution background art was compromised on the GBA's limited-resolution screen, and there was insufficient ROM space for the well-acted spoken dialogue to be heard. While I was very happy to see a proper adventure game released on the GBA, in practical terms it didn't fully engage me at the time.

With this new approach I'm trying, there are likely to be *** NO MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD ***, just so you know.

Here's the obligatory title screen shot:

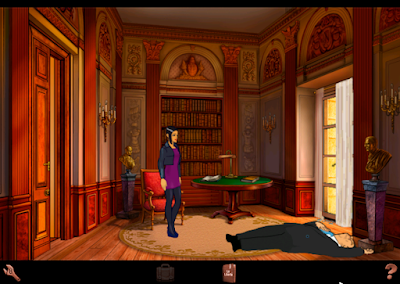

And here's the beginning of gameplay, a moment unseen in the 1992 version, as a prologue to the original narrative confronts Nico with the murder of a family friend. The visual style of Broken Sword 1 is impressive and the Director's Cut release increases color depth a little, so even though the game isn't in full HD resolution the lighting and details look great in every scene.

I really enjoyed this game -- I knew it by reputation and that reputation proves well-deserved. It definitely contains plenty of humor borne out of the many eccentric characters our hero George Stobbart encounters, but it's generally serious in tone with some dark story elements and well-plotted twists and turns. The plot has to do with the Knights Templar, or so it seems, and a trail of obscure clues and puzzles that the player must follow to reach the story's satisfying conclusion. The game features traditional point-and-click inventory puzzles and conversation-driven progress, but also has some visual puzzles involving decoding simple ciphers and positioning mechanical elements to unlock or engage a mechanism. I appreciated these tactile puzzles -- they bring something new to the adventure genre beyond audiovisuals, and they break up the action while also raising the stakes a little with fresh challenges.

I won't go into detail on the plot, but will note that the story sprawls across multiple countries and continents. Each region is well-contained and it isn't difficult to focus on what's of practical value within each sub-section. Inventory is also nicely managed by the game design, leaving items behind once they've been used appropriately and reducing the number of "apply random object to random object" experiments a stuck adventurer has to attempt before a better idea emerges.

The Virtual Theatre engine Revolution Software developed and used in many of its 2-D games is a little different technically from the Sierra AGI/SCI engine and Lucasarts' SCUMM, in that it doesn't seem to support a fully "3-D" layering effect in the same way. There is often a foreground mask element that scrolls in parallax with the background in wider scenes and covers up the background and characters if they're behind it, but within a scene, the background is generally structured so the "floor" is completely open and there's never a need to place characters behind a part of the background. It's an interesting tradeoff -- it's more memory-efficient than Sierra's approach, avoiding the need to keep a background mask in unseen memory, and likely frees up CPU cycles for sprite scaling and managing multiple characters onscreen at once. I don't know the technical underpinnings in any detail, but there are definitely glitchy moments when George's character sprite covers part of the background that should be in front of him, and when animated characters overlap the one that is smaller/farther back sometimes appears on top of the one in the foreground. There are also no maneuvering puzzles -- all pathing is automatic, and the game saves time by going straight to the fadeout when an exit is selected. Honestly, I don't miss those particular engine features -- the Virtual Theatre approach forces cleaner visual design and makes gameplay a little bit more efficient, especially when the player is stuck and trying everything possible in a given area.

What else? The game took me about 18 hours to finish, and I did have to look up a playthrough to get myself unstuck at one point; as often happens in these games, I had the right idea but I hadn't quite followed the intended sequence of actions. And I very much enjoyed the journey and the genuinely exciting climax, even though player choices are a bit limited toward the very end and, as this is a player-death-free adventure game, the only available actions are the game-winning ones at a few key points. The animation is fluid and the characters' visuals and voices are full of personality.

Bottom line, I definitely have Broken Sword 2 - The Smoking Mirror: Remastered on my to-play list now, though I'll likely tackle something else in the meanwhile. Please feel free to comment about this type of post -- I'm hoping I can cover games that are still in circulation like this one in a way that isn't redundant with the rest of the online universe, but still brings some readable observations to the table.